The American Headquarters in Chadds Ford

Thanks to a group of local residents and historians who created the Brandywine Battlefield Park in 1949, visitors now can get insider’s feel for what life was like for residents of the Brandywine Valley in 1777.

The homes of Benjamin Ring and Gideon Gilpin were originally preserved because they served as the respected headquarters of General George Washington and the French Marquis, as Lafayette was often called.

New ways of examining historic sites, based on period documents – and not merely on community legend – has led to the park to place greater emphasis on the Ring and Gilpin families as representative Quakers whose homes reflected the best of 18th-century standards. Today the park keeps the homes furnished in an authentic colonial manner to preserve what park officials call the lifestyle of wealthy, open-minded Friends – each had family members who were so-called Fighting Quakers as well as “a good house, good land, and good-size family.”

Gilpin ran a tavern in his home after the war, perhaps to offset his financial losses. Ring had additional income other than farming. He had inherited the 150-acre farm from his father and later ran a fulling mill and sawmill across the road from his house. The core of the mill is now preserved and serves as the Chadds Ford Township building.

The Ring House

For three days beginning on Sept. 9th, 1777, the Ring House served as Washington’s headquarters. It was a relatively short time, but Washington’s accounting records suggest that the house was crowded with officers and members of the War Council who met and dined in the Ring parlor.

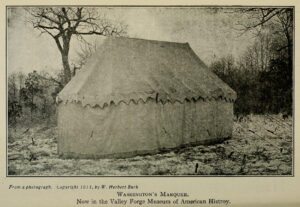

When Benjamin Ring was finally paid in February of 1778, he received 22 pounds that also covered the cost of a special dinner for Washington’s generals the night before the battle. Another account showed that Ring received 37 pound sterling and 10 shillings for Washington’s entire stay and that he was given the funds from “Col. Hamilton by the general’s order.” That is more than $2,000 in today’s currency. Gen. Washington may have slept in a tent at night, but even so the Ring family must have felt displaced. Ring’s wife, Rachel, was pregnant at the time with their eighth child.

After the Battle of Brandywine, Benjamin followed Quaker doctrine and didn’t file a damage claim. Still, historians say that distinct differences are found between Ring’s taxes in 1774 and in 1778 and that plundered items may have included 6 horses, 3 cattle, 6 sheep as well as 10 acres of crops and one servant.

The Ring House is of special interest to military historians since it is associated with both armies. It was a place where Washington’s Council of War developed their strategy to defend the area fords, among other crucial decisions.

An orchard on the Ring property was also the scene where fighting was described by historian Michael C. Harris as “hard, brutal, and short.” Harris is one of the few to document the orchard as the scene of another “bayonet to bayonet” clash. Harris races some of the men involved to those who fled Proctor’s redoubt above the Chads’ House after it was captured by the British late in the day.

Wayne’s troops (and perhaps the militia under Col. James Chambers) covered their retreat when Proctor’s artilleryman and reserve gunners fled away from the Brandywine and across the fields to the Ring farm.

Harris writes that the “presence of Chamber’s 1st Pennsylvania did little to stem the tide of advancing enemy troops, “ and quotes the American loyalist with the British, James Parker, who mentions the redoubt (the “fort”) as follows:

“Many of them [the Continentals] Ran to an Orchard to the right of the fort, from which they were Drove to a Meadow, where they made a Stand for some time in a ditch.” Parker continues to explain that the British troops continued to cross the Brandywine and routed the Americans from the ditch or “Meadow,” and “all afterwards was a mere Chace [chase], so far as I saw.”

The Queen Rangers that had captured the Proctor’s redoubt used the few guns that were left to attack the Americans below, perhaps Wayne’s defense along the Great Road to Nottingham, “our brave comrades cutting them up in great style,” as one Ranger recalled.

After the battle, the Rangers temporarily encamped on the Ring property. It was near the end-of-the day fighting in Chadds Ford and they no doubt were exhausted. The Rangers were said to have the most losses as any other unit; nearly 20 percent of its troops. The young ensign named Lord Cantelupe, who created a watercolor sketch of the action at Birmingham Hill, wrote that his unit waited the next day when they “marched 2 miles further to Dilworth [Dilworthtown, Pa], & there encamped.”

I